Patriot and Pacifist, Hollywood Stars, Seers of Nebulae

Edwin Hubble was born on November 20th 1889. Aldous Huxley died on November 22nd 1963 (the same day as JFK). While I missed both of these dates, this seemed like an opportune time to attempt to get the blog going again. What follows is an essay I wrote for the Griffith Observer and made available as a pdf online. While the Griffith Observer version is the official one (containing more pictures!) the pdf is fairly complete (also with additional pictures!) and this version has all the same text (but fewer pictures and poorer formatting!). The essay tells the story of what might initially seem to be an odd friendship between two major figures of the early 20th century intellectual scene.

Abysms of Space and Time

(Dedicated to Edwin Hubble)

by James Robert Allen

At the utmost limits yet attained

In inter-stellar space,

A giant eye sweeps through the sky

To find, perhaps, a trace

Of still more distant galaxies,

And plot their cosmic role,

where space may close, and thus disclose

The secret of the whole.

We travel aeons back in time,

When plumbing the depths of space,

Until we reach the ancient beach,

Where life began its race.

When light from faintest nebulae

That is reaching me

Began its course from distant source

No eye was here to see.

Fatigued, the lone observer sits

And waits and wonders, too,

What strange new thing the hours may bringing

Within his searching view;

What marvels inn uncharted deeps

May through the void be sown;

What shafts of light may pierce the night,

Beyond what now is known.

In the archives of The Huntington Library in San Marino1 are the diaries and correspondence of Edwin and Grace Hubble2 which recounts some episodes of their long friendship with another significant intellectual of the 20th century: Aldous Huxley. Eight miles to the northeast is the Mount Wilson Observatory, where Hubble did the work that would lead to immortal fame as manifested in the eponymous massive space telescope and law describing the universe’s expansion. The Hubble constant,3 \(H_{0}\), measures the linear correlation between the proper distance of a galaxy, or nebula as he preferred,4 and its velocity of recession. Hubble provided conclusive evidence that this correlation is linear. Hubble experimentally confirmed that nebulae are indeed external star systems rather than only cosmic dust or faint stars in the Milky Way and that these nebulae are traveling away from us. These results led Einstein to give up what he (probably) called the “biggest blunder of my life”, the cosmological constant, which he had put into the original field equations of the general theory of relativity in order to preserve his conception of the universe as “steady-state”—neither expanding nor contracting.5 The need to explain the high velocities of the distant nebulae led concurred with a theory of a highly inflationary period in the early universe, known as the “Big Bang”.

Though he lacks such scientific contributions of the first rank, Aldous Huxley was uncontroversially considered a man of science.6 The influence of science suffuses Huxley’s entire body of work. His best known work, A Brave New World, portends a dystopia brought on by technological advancement and a scientific-cum-eugenic approach to life. Aldous Huxley had his interest in science start close to home, being the grandson of early evolutionary theorist Thomas H. Huxley, “Darwin’s Bulldog”. Scientific and literary achievement seems to run in the Huxleys’ blood: Aldous’ brother, Julian was an evolutionary biologist like their grandfather, their great-uncle was poet and critic Matthew Arnold, and Aldous and Julian’s half-brother Andrew, won the Noble for physiology or medicine in 1963. Over the course of Aldous Huxley’s career his attitude towards science ran the gamut from alienation, to enthusiasm, to cautious endorsement; he was well aware of the promises and risks of science for the person, literature, and society as a whole.7 Of particular interest here is his turn to mysticism in the 1930s which coincided with his expatriating in Southern California, and so with his friendship with the Hubbles. Huxley’s increasing engagement with and acceptance of mysticism was not made at the expense of his scientific outlook. As will be shown his mysticism was an extension of his thoroughgoing empiricism, a philosophy of science he shared with Edwin Hubble.

Hollywood Stars

For all their similarities in matters of epistemology, Edwin Hubble and Aldous Huxley were at odds politically, especially regarding the second World War. The distinction between Hubble the patriot and Huxley the pacifist is well illustrated by the differences in their paths to Hollywood.8 Hubble served as as an officer in the first World War, applying to join the army immediately. Though Hubble impressed and rose to the rank of a major, he did not, much to his chagrin and probably to astronomy’s benefit, see much, if any action.9 Upon Hubble’s return from his service as an officer—and an intermission spent studying astronomy in Cambridge—he went to Southern California to take up the job saved for him at the Mount Wilson Observatory.

Hubble would later work as the Head of Exterior Ballistics at the Aberdeen Proving Ground during the second World War. Hubble was in favor of the war even prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor; Hubble made radio broadcasts and speeches in favor of war.10 Hubble was awarded a Medal of Merit in 1946.11 Interestingly, after the war—after the bomb—Hubble adopted a pacifist stance: the next war must not happen. His pacifism remained practical; he had pacifist ends and not means—in contrast to the absolutist pacifism endorsed by Aldous Huxley, as presented in his (1937) Ends and Means. Hubble understood that the abolishment of war required a global sovereign with police powers.12 War cannot be deterred except by the threat of war.

Huxley, on the other hand, was never military material owing to his poor eyesight.13 Inspired by his friend Bertrand Russell, Huxley became a conscientious objector rather than a reject during World War I conscription. In contrast to Russell, Huxley maintained his pacifism in the run up to war during the thirties. Pacifism took on a religious significance for Huxley. His political commitment lead to his denigration by the Stalinist Left and the Nationalistic Right, and with the onset of the Spanish civil war Huxley was alienated even from his natural allies, anti-Fascist anarchists. Leaving England, Aldous, his wife Maria (née Nys), and his closest friend, fellow pacifist and Oxonian Gerald Heard escaped from an increasingly politically hostile environment. Huxley and Gerald planned a speaking tour, founded on the hope his pacifist message would be more efficacious to a then neutral and isolationist America. Huxley also hoped to be able to make a lot of money writing for the movies.14

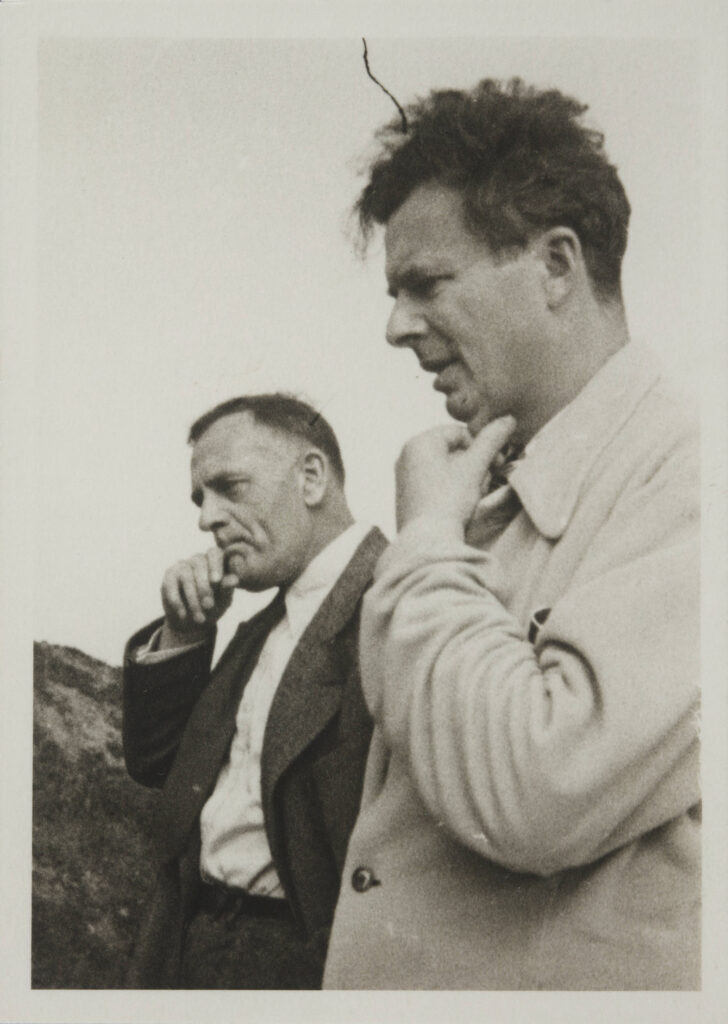

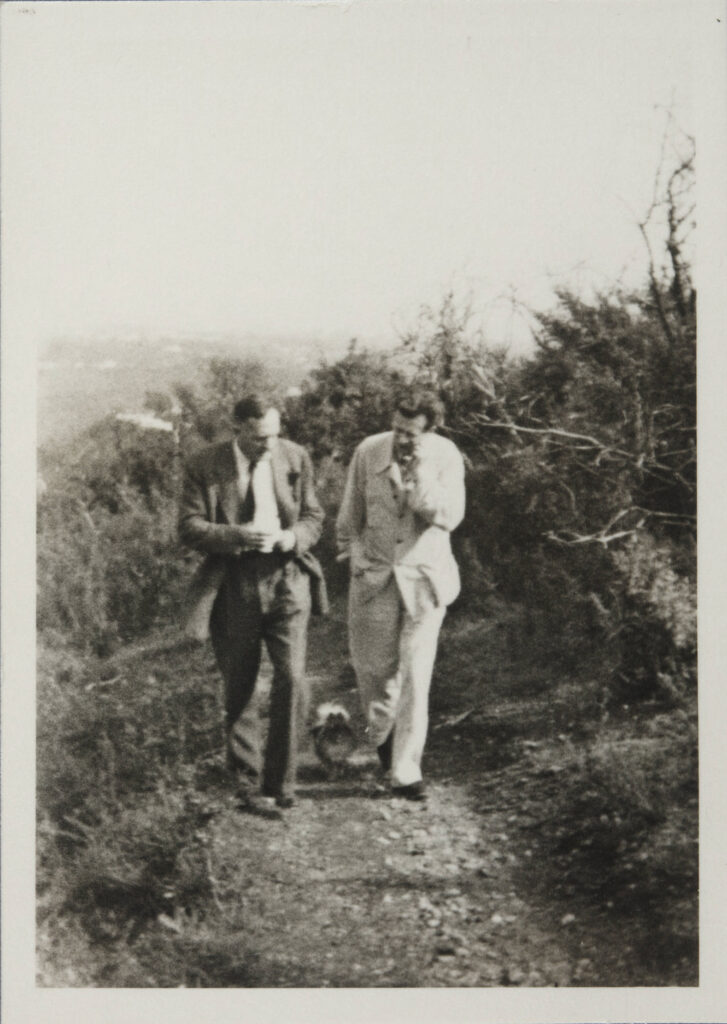

In the cultural and social network that comprised Old Hollywood, Hubble and Huxley developed a friendship in close proximity to some of its central stars, like Greta Garbo, Charlie Chaplin, and Paulette Goddard. Their close circle also included the novelist Christopher Isherwood, actress and writer Salka Viertel, and the woman who brought the two couples together, Anita Loos—author of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, among many other films and plays. It was a picnic organized by Loos that began the lifelong friendship between the two couples.

In Aldous and Edwin’s relationship political tensions regarding the war mostly hummed in the backdrop— they retained a personal and intellectual relationship. Though I have found reports of discussions regarding astronomy and other scientific manners, not least of all a Christmas conversation with Bertrand Russell,15 I have failed to find anything specific. There is at least evidence of Huxley raising some of his more esoteric interests to Edwin Hubble’s attention, but no letters in response from Hubble are known to me regarding his opinions of animal magnetism, telepathy, and prevision. In this connection, Huxley mentions William Herschel’s experience of an alternative form of consciousness during his visions of geometrical figures—presumably meant to appeal to the fact that Herschel was one of Hubble’s great astronomical influences.16

What follows is then, not an examination of these two figures direct intellectual confrontation, but an investigation into a an intellectual parallel: a common empiricist epistemology. While their objects of focus were distinct, outer space and the nature of the mind, their method was the same—it was the art of seeing.17 It is important in this regard to emphasize what it means to take observation as an art, a matter of technique, rather than accepting a naive empiricism, as neither Huxley nor Hubble did. To hold seeing as an art means to aim at perfecting it, through the development and interrogation of the tools one uses for seeing. In Hubble’s case, the tools of sight were telescopes, photography, and spectral analysis and the interpretation of the various luminosities of various spectra were the given to be interrogated with reason and mathematical technique. Huxley became increasingly concerned with the preconditions of sight and observation at all, the processes of the mind:

Ever since ophthalmology became a science, its practitioners have been obsessively preoccupied with only one aspect of the total, complex process of seeing—the physiological. They have paid attention exclusively to eyes, not at all to the mind which makes use of the eyes to see with. (Huxley 1971, 1)18

Hubble and the Expansion of the Observable Universe

Much like the author of Brave New World, Edwin Hubble had wide interests19 and was particularly concerned with the relationship between science, technology, and society. His concerns with politics appears in his early support for the war against Hitler; One speech from 1941 closes:

We all want peace. But it must be peace with honor. Peace at any price is a religion of slaves. The freedom we cherish is a heritage from brave men who the world over, since time began, have fought to establish and maintain it. If there is one lesson that history has taught us, it is this, strong men can determine their own destiny (HUB 39, p 13)20

In contrast to Hubble’s acceptance of the most thoroughgoing conditions of citizenship, defense of a nation and way of life, Hubble understood his practice as a scientist independent of his role as a citizen, in his view:

Let me begin with an attempt to emphasize the distinction between science and values, a distinction which is evident in a comparison, for instance, of the laws of motion and the canons of art. The realm of science is the public domain of positive knowledge. The world of values is the private domain of personal convictions. These two realms, together, form the universe in which we spend our lives; they do not overlap. (Hubble 1954, 6–7)

Hubble’s strong distinction of the world of positive facts from the world of values—what is often known as the value-free ideal of science—does not preclude scientists from having moral in additional to epistemic duties. He was concerned with the threat of modern science dominating civilization. Applications of scientific knowledge need to be controlled rather than the other way around and so:

Th[e] clarification of the problem which overshadows our civilization is the first duty of the scientists. The solution of the problem, and its enforcement, are the responsibility of all men—including the scientists, but only in their position as human beings, not as specialists. (Hubble 1954, 5)21

That said, Hubble is generally a positivist about science: its progressive nature is what distinguishes it from other intellectual endeavors like poetry or moral philosophy. His philosophy of science reflects that as an astronomy, he works in “the type specimen of pure science”; besides values, technology is distinguished from scientific knowledge, of which it is an application.

Hubble’s empiricism reflects his role as a practitioner of the observational approach to cosmology (the title to his (1937) Rhodes Lectures). Within pure science there is the theoretical and the experimental or observational. For Hubble the results of the latter are prior to and more stable22 than the results of the latter. Contrary common usage in the philosophy of science, Hubble preserved the term “law” for observational laws, empirical generalizations, as opposed to theories which form unifying superstructures of observed laws, providing some unified explanation. As such, these theories are always accepted as temporary working hypotheses which successively better fit and explain the phenomenal laws, and “in this way, science proceeds as a series of successive approximations.” (Hubble 1954, 15) That science is limited to the phenomena explains its success and progressive nature. Hubble invokes Eddington’s tale of the fisherman who catches only fish greater in two inches in length; this has been determined a priori, for his netting has two inch holes. So is the same with reality: we only can observe those features which our sensory apparatus filters from the totality of the world. Hubble was well aware of the limitations of observational astronomy, our conclusions about the nature of the universe as a whole will only ever be speculation from the lawful patterns found in the observable part of the universe.

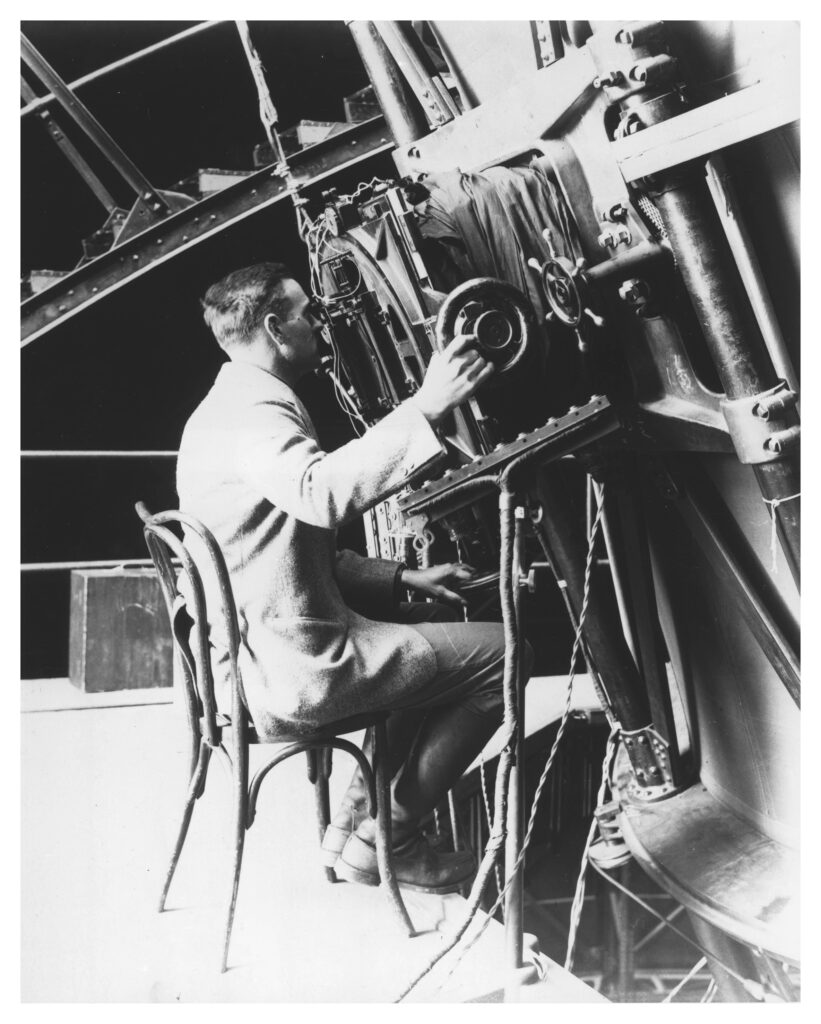

Hubble’s work, described in the awarding of his Franklin medal in 1939 as “[having] extended the spatial frontiers of human knowledge in a greater proportion than any other in the history of science”,23 proceeded in two major steps. First, with the power of the 100-inch Hooker telescope on Mount Wilson, Hubble was able to resolve nearby nebulae into groups of stars and determine their properties by their relative numerosities—this in turn allowed for the analysis of Cepheid variables, which are stars which oscillate in luminosity. Hubble used Shapley’s relation between the period of the oscillation and the luminosity of the Cepheids to determine their distance. Cepheids in the Andromeda neblua were then compared to the local group, determining their distance to be hundreds of thousands of light years away; this confirmed the existence of nebluae beyond our galaxy.24 Second these distance measures were then applied to further and further out nebluae (hundreds of millions of lightyears away), whose spectra were found to be red-shifted. The correlation between faintness (inverse luminosity) which measures distance and the degree of red-shift is well established observationally, and Hubble systematically showed that this correlation is linear. Usually red-shifts and spectra are attributed to the Doppler effect, meaning that these observations would define a correlation between distance and velocity. However, alternative explanations, like scattering, needed to be eliminated which required the recruitment of corrections from curvature predicted by the general theory of relativity (if \(R > 0\)). This and the need for further assumptions regarding the density of matter in space, led Hubble to caution disregarding the underdetermination of theory by the available evidence—red-shifts may have some other explanation.

It is noteworthy to consider that Hubble practically never put forward major any novel hypothesis (the island universe hypothesis was already speculated by Kant, following Thomas Wright);25 Hubble’s major contributions were to provide novel standards for accurate measurement and therefore stronger evidence for the existence of a universe of galaxies beyond the Milky Way and the expansion of the universe. Hubble brought philosophical speculation down to Earth and within reach of our homely sense organs.

That science is limited to the phenomenal world, the world of facts which are possibly universally agreed upon,26 does not mean that Hubble totally excluded the mystics knowledge of the Absolute, the Given, the noumena. Hubble’s attitude was Kantian,27 he always limited himself to the observation and held theoretical speculation about reality itself at arm’s length. In the close of his essay “The Nature of Science”, Hubble raises raises the possibility and the primary problem facing knowledge of reality an sich—just of the sort that Aldous Huxley claimed to have experienced under the influence of mescaline, in the year of Hubble’s death:

[T]hat world which science cannot enter, has no concern whatsoever with probable knowledge. There finality—eternal, ultimate truth—is earnestly sought. And sometimes, through the strangely compelling experience of mystical insight, a man knows beyond the shadow of a doubt, that he has been in touch with a reality that lies behind mere phenomena. He himself is completely convinced, but he cannot communicate the certainty. It is a private revelation. He may be right, but unless we share his ecstasy we cannot know.” (Hubble 1954, 18–19)

Huxley and the Expansion of the Mind

“Psychedelic” combining the Greek words for mind (“psyche”) and visibility or clarity (“delos”) has the conjoint meaning mind-revealing or mind-manifesting. This term was coined in correspondence between Aldous Huxley and Humphrey Osmond, the doctor who gave Huxley his first hit of mescaline some three years prior to the word’s baptism. It was this mind revealing power drew Huxley to his direct investigation of the psychedelic experience, led to Huxley’s full embracement of mysticism. Huxley’s first trip was immortalized in his popular Doors of Perception.28 While Huxley, like many mystics before him, held that the knowledge gained from mystic experience was beyond scientific knowledge, which betrays the purity of experience, Huxley’s approach to mystical experience was scientifically motivated. His motivations were above all, empiricist. For Huxley, the various reports of mystics and the subjects of what we call “limit experiences”,29 could not be believed, nor understood, without direct observation of the phenomenon itself. The psychedelic experience, Huxley found, is characterized by a cleansing of the “doors of perception”,30 the categories, concepts, prejudices, and habits of thought that prevent us from seeing things as they truly are.

Aldous Huxley had come a far way from the youth who was described by his more scientifically inclined friend, J. W. Sullivan as one who “frankly cannot understand religious people and he finds the scientific mind unsympathetic”.31 Huxley’s project from this time on would be to find a synthesis of mystic wisdom and rationality that could serve as a guide to society—a partial illustration being provided in his final novel, Island (1972). He was likely influenced by Sullivan’s tendencies to understand the new physics as evidence for metaphysical idealism, and his characterization of Maxwell as a mystic in the “teeth of Victorian materialsim”. Huxley even made a visit, following in Faraday’s footsteps, to Pietramala—in the eponymous travel essay he claims he would rather be reborn as Faraday than as Shakespeare.32 Even though he turned away from the scientism of Sullivan, Huxley’s exposure to possibility of reconciling the mystic and the scientific would influence him for the rest of his life.

Huxley’s empiricism was not, however, naive. He was aware of issues like the underdetermination of theories by data and the role of aesthetic values in accepting a scientific theory. Huxley’s own philosophy of science comes closest to a species of pragmatism, in way like that of another scientific and philosophical mystic, William James.33 Though Huxley accepted the theory-ladenness of ordinary observation, the mystical experience was epistemically privileged. The mystic, shorn of ego, positively identifies with the One or Great Mind that is at the ground of Being—this is a “pure experience” of the Given. James describes pure experience so:

‘Pure experience’ is the name which I gave to the immediate flux of life which furnishes the material to our later reflection with its conceptual categories. Only new-born babes, or men in semi-coma from sleep, drugs, illnesses, or blows, may be assumed to have an experience pure in the literal sense of a that which is not yet any definite what, tho’ ready to be all sorts of whats; full both of oneness and of manyness, but in respects that don’t appear; changing throughout, yet so confusedly that its phases interpenetrate and no points, either of distinction or of identity, can be caught. (James 1912, 93–94)

This we can compare to Huxley’s own description of his experience:

I took my pill at eleven. An hour and a half later, I was sitting in my study, looking intently at a small glass vase. The vase contained only three flowers—a full blown Belle of Portugal rose, shell pink with a hint at every petal’s base of a hotter, flamier hue; a large magenta and cream colored carnation; and, pale purple at the end of its broken stalk, the bold heraldic blossom of an iris. Fortuitous and provisional, the little nosegay broke all the rules of traditional good taste. At breakfast that morning I had been struck by the lively dissonance of its colors. But that was no longer the point. I was not looking now at an unusual flower arrangement. I was seeing what Adan had seen on the morning of his creation—the miracle, moment by moment, of naked experience. (Huxley 1954, 16–17)

What Huxley calls here naked experience or “Is-ness” or “Suchness” is a realm of experience prior to conceptual and scientific understanding, much like James’ pure experience. This is not to say that Huxley thought there was no such thing as mystical knowledge as such, though knowledge tends to require concepts. On the contrary the knowledge of pure experience yields enlightenment and moral benefit—it is a knowledge bereft of the distorting effect of our processing apparatus:

We must learn how to handle words effectively; but at the same time we must preserve and, if necessary, intensify our ability to look at the world directly and not through that half opaque medium of concepts, which distorts every given fact into the all too familiar likeness of some generic label or explanatory abstraction. (Huxley 1954, 75)

Huxley argues that the absence of such knowledge in dominantly verbal education is costly; his final novel, Island, attempts to describe a utopia wherein the ritual use of the psychedelic “moksha” holds a pedagogical purpose.

What is the nature of this mystic knowledge? What is its content? Here Huxley runs into the old problem of the mystic: expressing the inexpressible. Though our homely words and concepts are not fit to task, Huxley does provide descriptions of that “obscure knowledge” of the unity of existence:

This given reality is an infinite which passes all understanding and yet admits of being directly and in some sort totally apprehended. It is a transcendence belonging to another order than the human, and yet it may be present to us as a felt immanence, an experienced participation. To be enlightened is to be aware, always, of total reality in its immanent otherness—to be aware of it and yet to remain in a condition to survive as an animal, to think and feel as a human being, to resort whenever expedient to systematic reasoning. Our goal is to discover that we have always been where we ought to be. (Huxley 1954, 77–78)

The enlightenment gained from mystical experience is, in the ideal, to be integrated with scientific and practical knowledge rather than replace them. For Huxley the mystical experience was not in conflict with the world of ordinary experience, but rather it is to inform, guide, and transfigure our experience of the world to one with meaning.

Experiment and Experience

What this examination of the empiricism of Edwin Hubble and Aldous Huxley shows is that beyond a mere theoretical position, empiricism is a guide to action and to investigation. Though their objects of study were robustly different, they both had a drive to explore the deep nature of the world around them using whatever experimental tools they found useful. Neither man finished his life finding his curiosity satisfied, as a good empiricist is always left with some degree of doubt:

Thus, the explorations of space end on a note of uncertainty. And necessarily so. We are, by definition, in the very center of the observable region. We know our immediate neighborhood rather intimately. With increasing distance, our knowledge fades, and fades rapidly. Eventually, we reach the dim boundary—the utmost limits of our telescopes. There, we measure shadows, and we search among ghostly errors of measurement of landmarks that are scarcely more substantial.

The search will continue. Not until the empirical resources are exhausted, need we pass on to the dreamy realms of speculation. (Hubble 1936, 201–2)